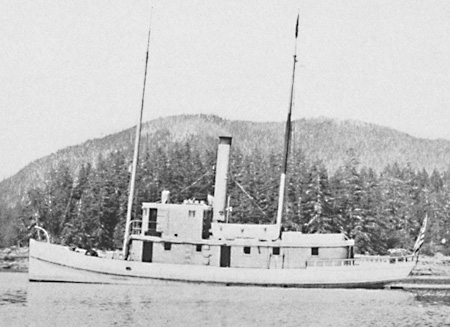

US Osprey

AFSC Historical Corner: Osprey, BOF’s first Alaska patrol boat

The steamer Osprey. Bureau of Fisheries photo, 1914. |

With the urgent need to protect Alaska’s fishing products valued at

nearly $17 million in 1911, the Bureau of Fisheries (BOF) acquired its

first patrol vessel. In the fall of 1912, the coal-burning steamer

Wigwam was purchased for $13,000 from the Alaska Packers Association,

who had previously rebuilt the ship to top condition in compliance with

the Steamboat-Inspection Service’s recommendations. Prior to her BOF

service, the “little old steamer” was “one of the first cannery tenders

to operate in the Alaskan salmon packing business.”

(Petersburg Weekly Report, Alaska, VII:17, 4-8-21, p. 1.).

The vessel was renamed the Osprey by the Bureau and kept upon the ways at Semiahmoo, Washington, where it awaited Congressional appropriation for a crew prior to her commissioning. On 1 July 1913, the appropriation was effected and seven days later the Osprey sailed north to begin patrol work and other duties in the southeast district of Alaska. Her six-man crew consisted of the master, engineer, two firemen, seaman, and cook. By the end of 1913 over 8,000 miles had been logged.

Built in 1895 in San Francisco, California, the Osprey was equipped with a steam winch on the forward main deck and had two masts. The pilot house area on the boat deck quartered three crewmen, while immediately beneath were the galley and dining room on the forward main deck. Six of the crew could be quartered in the below forecastle and four more could be accommodated in the after cabin which had folding berths and was finished in Spanish cedar.

The vessel experienced several difficulties during her service with the Bureau. A major concern was soon expressed that the engine should to be converted to oil or gas. With the afterhold being impractical for holding additional sacks of coal, the Osprey had limited bunker space which allowed stowage for only 7.5 tons of coal. This resulted in a steaming radius amounting to about 350 miles, much less than the distance required for the demanded service. Another factor was that the cost of coal at that time was $8.50 to $12.75 a ton and was usually obtained at Unalaska on the Aleutian Islands. It was estimated that an engine conversion would save up to 90% in reduced fuel costs.

In addition, a problem with using coal was that the smoke emerging from her stack easily identified the ship from afar. This provided an early warning to those in violation of the fishery laws since there were very few steam-powered cannery tenders in operation at that time in the area. The BOF never did replace the Opsrey’s aging and problematic boiler, opting rather to make the necessary repairs when required.

The Bureau also found it hard to retain good crewmen aboard the vessel because provisions for subsistence allowances were not included in the fixed pay rates established by Congress. After paying his mess expenses, a crewman, who in 1914 was earning $50-$60 a month, found himself left with too little pay to be considered incentive for employment. The need was also expressed for the crew to be increased by one or two seamen for the necessary ship maintenance during the constant running while on active patrol duty.

Another mark against the Osprey was her poor state. After inspectors George H. Whitney and Peter A. Peltret surveyed the vessel in 1915, it is believed that she was scheduled to be condemned at Ketchikan, Alaska, due to her unseaworthiness. She somehow avoided this fate and was kept in service for another five years.

Over the years the Osprey was headquartered in Juneau, Alaska, while maintaining the enforcement of the salmon fishing laws and regulations in the southeastern region during summer seasons. In 1916 she was used at Wrangell, Alaska, for stream investigation work in the spring and then was sent to Seattle, Washington, in October for repairs. The vessel remained in Seattle for over a year until January of 1918 when she returned to Alaska.

In 1918 the Osprey participated in two notable rescues in Alaska. Late in the spring, she towed the boat Good Tidings – in danger after breaking down during a storm – 10 miles to Ketchikan. Then in late October and most of November, the Osprey joined the BOF vessels Auklet and Murre in Alaska to search for bodies from the Canadian Pacific steamship Princess Sophia, which struck Vanderbilt Reef on 25 October, losing 343 lives with no survivors.

In June of 1919, the Osprey was transferred to Alaska’s central district where she patrolled until August, at which time she was sent to be laid up at Cordova. The vessel proved unseaworthy to the point that no further significant expenditures were made in her upkeep. It was also decided to condemn the boat and sell her after another year of service.

The Osprey was beached near Cordova in the spring of 1920 to have her hull cleaned and copper painted. On 25 May, in what seemed like an act of defiance, the Osprey settled in the gravel, fell over on her side away from the shore, filled with water and was partially submerged. She remained this way for about a week until the Coast Guard cutter Algonquin was able to render assistance. A scow owned by the Bering River Coal Company was then used to float the Osprey so that the water could be bailed out of her. For next few months she was used in the southeast region for summer patrol and salmon stream marking work in September. She left her Alaska service, towed by the Auklet to Seattle for disposition.

The newspapers in Seattle and throughout Southeast Alaska advertised the 14 April 1921 public auctioning of the Osprey. Two credible sources give conflicting details of the sale:

-

Poor attendance for the sale produced a high bid of only $515, which was rejected as being too low. On 29 June, the vessel was again auctioned and sold for $700 – buyer unknown. (BOF Fisheries Service Bulletin, May 1921);

-

“Wrangell, April 14 – The United States Fisheries boat Osprey was sold at public auction here today to Mayor J.G. Grant for $550.” (The Alaska Daily Empire, Juneau, 4-14-21)

After the sale it appears that the owner (Mayor Grant?) may have restored the the ship’s name back to the Wigwam. Operating as a tug, she was sold by 1922 to the Foss Launch and Tug Company. Foss rebuilt the vessel into a more seaworthy tug renamed the Foss 19. After her steam plant was finally replaced with a 180-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse diesel engine, she began many years of tug duties and general towing in Puget Sound and Southeast Alaska out of Ketchikan. She became the first Foss tug to work in Alaska (Skalley).

|

| Two views of the diesel tug Foss 19 before and after her 1940 deckhouse remodel – significantly changed since her Osprey days with the BOF. Top: Foss Maritime Co. photo. Bottom: from Pacific Motor Boat, Dec. 1947. |

At the end of the 1930’s, the Foss 19 began hauling oil each year to communities in Southeast Alaska. Around 1940, her engine was upgraded to a 200-horsepower Enterprise full-diesel and additional overhauling and modernizing of the boat’s deck house and cabins was done. With this engine the Foss 19 often won tugboat races she competed in during the 1950s (Newell).

The Foss 19 continued her service with Foss until she was sold on 14 May 1965 to Pat Stoppleman who renamed her the Kiowa and installed a replacement D-343 Caterpillar engine. Two years later in 1967, Samson Tug & Barge purchased the boat and operated her out of Sitka, Alaska.

On 30 October 1978, the tug found herself in heavy weather while pulling logs in Herring Bay (Frederick Sound, near Ketchikan). The vessel floundered and sank after logs, which had broken loose from the load, tore open her stern in the rough sea. Fortunately, the crew was rescued by another Samson tug before the Kiowa was lost (Skalley).

- Newell, G. 1957. Pacific Tugboats, p.140. (Photographs from the Joe

Williamson marine collection). Bonanza Books, New York, NY.

- M. R. Skalley, M. R., 1981. Foss 90 Years of Towboating. Superior

Publishing, Seattle.

The Foss 19 seen listing ashore near logs. Photo from the Captain Lloyd H. "Kinky" Bayers collection, 1898-1967: book 32, album 16, photo 2. Alaska State Library Historical Collections. |

| A Poor Evaluation |

| The Osprey was considered to be well constructed, however, after the Bureau's Deputy Director, E. Lester Jones, lived aboard her for 60 days during his 1914 inspection of the Alaska fisheries, his opinion of the vessel was unfavorable. In his Report of Alaska Investigations, 1914 ( .pdf, 17.4 MB) Jones expressed the following: "In reference to the unseaworthiness of the Osprey, I feel well qualified to pass judgment, for in my investigations and research this season I lived aboard her for 60 days and found conditions far from satisfactory. Her freeboard amidships is just 12 inches. From the deck to the top of the pilot house the distance is over 14 feet, and with the greater part of her machinery above the water line the vessel is so topheavy that a good breeze renders it dangerous to leave the dock. In an unusual blow last fall, the Osprey without warning turned completely on her side, lying flat on the water long enough for the engine room to be flooded. The officers and crew were penned up in this treacherous boat, and only by an act of Providence did a counter flurry right her in the next few seconds. This is the vessel that is offered to our men to patrol 26,000 miles of coast line in boisterous seas to protect the great fishing industry of Alaska. The decks, pilot house, and many of the beams are rotten, and the boat must be handled with unusual care. The boiler is also defective, having been installed 19 years ago, when the boat was built. However, I talked with men of experience who are familiar with vessels and their construction, and all admit that her hull is strong and sound and agree that this boat if properly refitted and provided with more efficient machinery would prove suitable for certain requirements of the Alaska patrol service... The Osprey has been used only part of the time during the last two years in southeastern Alaska, due primarily to two reasons first, lack of appropriations; and second, because she is unseaworthy and many days unable to leave her dock." |